«I think it’s impossible to make any movie without it being about race, because race is all around us. You can’t have Black people in a flying saucer film and just have it be the same experience. It’s not. There’s a different relationship.»

Jordan Peele

This article will conduct a comparative study of the films Get Out (2017) and Candyman (2021), and their direct correlation to contemporary social issues such as the Black Lives Matter movement, police brutality or gentrification.

Get Out is a psychological horror film that follows the story of a young African-American man called Chris. His white girlfriend, Rose, invites him for a weekend getaway at her family estate with her parents. At first, Chris –played by Daniel Kaluyaa– reads the family’s overly accommodating behaviour as nervous attempts to deal with their daughter’s interracial relationship, but as the weekend progresses, a series of increasingly disturbing discoveries lead him to a terrifying truth. Disturbing scenes follow one after the other, increasing Chris’s tension as he begins to suspect that something is wrong. He finds photos of Rose in prior relationships with several black partners contradicting her earlier claim that Chris is the first black person she has dated. He tries to leave the house, but Rose and her family lock him in. Their objective? To empty his mind and sell his body as a vessel for the conscience of some wealthy white man. (Monkeypaw Productions, n.d.-a).

The film, written, directed and produced by Jordan Peele, was critically acclaimed for its technical and artistic qualities, but above all for its social critiques. Furthermore, it was a major commercial success, considering its budget of $4.5 million and its gross of $255 million (Get Out, n.d.). In addition, at the 2018 ceremony, Peele took home the Oscar statuette for Best Original Screenplay (The 90th Academy Awards | 2018, n.d.).

Candyman, released 4 years after Get Out, is a supernatural slasher horror film directed by Nia DaCosta; written by herself, Win Rosenfeld and Jordan Peele; and produced by Jordan Peele, Win Rosenfeld and Ian Cooper. The film, which is a direct sequel of its 1992 homonymous, uses its horror elements to make a critique of the racial social injustices happening in America, in this specific case in Chicago. Addressing issues such as gentrification or police brutality along the way, the film tells the story of Anthony (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), a budding African-American artist who becomes obsessed with Candyman, a mythological character from the neighbourhood and its urban legend: by saying «Candyman» five times to a mirror, its spirit will appear and kill the summoner (Monkeypaw Productions, n.d.-b).

Despite being two quite different films (considering that Get Out is more psychological and Candyman a supernatural slasher), both have important qualities in common: they use horror as a mirror of racial social injustices. And it seems on point to discuss these topics inside the horror genre as a reflection of the horror that black people have historically faced.

As Alison Landsberg points out in his article about the film, Get Out “uses the clunky and often artificial mechanics of the horror genre in order to expose actually existing racism, to render newly visible the very real but often masked racial landscape of a professedly liberal post-racial America” (2018).

In fact, one of the most applauded aspects of the film is its ability to portray the latent racism in the liberal American population. Lanre Bakare describes it very accurately: “The villains here aren’t southern rednecks or neo-Nazi skinheads. They’re middle-class white liberals. The kind of people who read this website (The Guardian). The kind of people who would have voted for Obama a third time if they could. The thing Get Out does so well – and the thing that will rankle with some viewers – is to show how, however unintentionally, these same people can make life so hard and uncomfortable for black people. It exposes a liberal ignorance and hubris that has been allowed to fester. It’s an attitude, an arrogance which in the film leads to a horrific final solution, but in reality leads to a complacency that is just as dangerous” (2018). Rose’s family may seem progressive, but it portrays the typical self-congratulatory American family, which does not consider itself racist, but shows no deep interest in understanding what their fellow African-Americans have to go through (Get Out Explained: Symbols, Satire & Social Horror, n.d.).

The film constantly alludes to the racial history of the United States. In his article, Abdul Moiz highlights two specific scenes. The first is the bingo scene, in which Chris’s body is being auctioned off, a clear reference to the slave trade. The second more significant scene for Moiz is when Chris is picking cotton out of his chair; another clear reference to the slave trade (2021).

Get Out drew many comparisons with Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, the classic starring Sydney Poitier. However, where the classic doesn’t go (due to the socio-cultural context of the time), Peele dares to go in without a second’s hesitation. Long before the real terror of the film is unleashed, Get Out makes you suffer and even terrifies. How is that possible? By showing the overwhelming reality of micro or indirect racism.

On the other hand, Candyman has numerous references to social issues such as gentrification. This term is usually used “to describe examples of “urban renewal” in which wealthy—usually white—new residents are rewarded for “improving” an old deteriorating neighbourhood at the expense of lower-income residents—typically people of colour—who are driven out by soaring rents and the changing economic and social characteristics of the neighbourhood” (Gentrification: Why Is It a Problem?, 2021). The film revolves around Cabrini Green, a Chicago neighbourhood historically associated with its African-American population. However, with the modernization of the neighbourhood, there now seems to be no place for the people who founded it. In the midst of this context, Nia DaCosta presents us with a Black protagonist who lives in a hip apartment with his fellow artistic-minded girlfriend (Farrell, 2022). This creates a really interesting dichotomy, as Anthony and his girlfriend are contributing to the aforementioned gentrification.

A particularly important scene in the film is when the police brutally murder Sherman Fields, a hook-handed black man whom the police believed responsible for putting a razor blade in a piece of candy that resulted in the death of a girl. Police beat Sherman to death. It is later revealed that children continued to receive razor-bladed candy, which is why Sherman’s innocence is proven. This scene is really powerful because it evokes comparisons with the George Floyd murder, which took place just 1 year before the release of the film.

In addition, and as Feel points out, although in the first two candyman films the victims were plenty and there was no discrimination, the 2021 film’s victims were all white and represented some of the stereotypical racists behaviours. Taking the first murder scene as an example, “as Candyman is about to murder the art dealer, he slices through a projection screen showing Black people being violently attacked in the 50s during a protest; clearly, he is done with the historical injustice and ready for blood. Not only that, but the different parts of the art space flash red, white, and blue which could represent the American flag or police lights as the victims are being slain” (2021).

These social denunciations made by the film are all the more relevant given the socio-cultural context in which the film was released. In 2021, Black Lives Matter was coming from one of its highest (if not the highest) peaks. The movement, which began in 2013 following the murder of George Zimmerman, grew as more police killings took place (like Eric Garner or Michael Brown) and reached its peak in 2020, following the murder of George Floyd. Millions of people began to demonstrate around the world, in support of equality and against racial and social injustice (Campbell, 2021). Considering that Get Out was released in 2017 and Candyman in 2021, the influence of the social context on the films is clear.

One of the most interesting aspects of Nia DaCosta’s film is its ambiguity. Of course the main enemy is white supremacy and police brutality, but that is in abstract terms until the end. At first one may think the villain is Candyman, but it is not very clear what his motivations are. It’s in the climax of the film when it is revealed that Burke has an interest in Anthony becoming the new Candyman, yet another in the multitude of incarnations. Burke could then be seen as the «villain». DaCosta, Peele and Rosenfeld’s script continues to play with this duality (as it did with gentrification), in which its protagonists fight for what they believe in without falling into stereotypes. Burke believes that the best thing for the city is for Candyman to return, transformed into a kind of anti-hero. Anthony wants to be a successful artist, and along the way he loses himself and becomes obsessed with Candyman. Brianna wants to save Anthony from becoming Candyman. The ending is a grey zone, a conflict of interests, a whirlwind of all these intentions, more or less justifiable, but at least genuine. But the police arrive, shooting first and asking questions later. It is a most harrowing portrait of the reality of the contemporary African-American community, where their interests and motivations (which may be perfectly questionable as they are human) are subjugated by white supremacy.

One aspect of both films is the extreme use of violence. Chris is forced to kill Rose’s family in order to escape. It is true that with Rose dying on the ground in the final scene, it was not necessary to strangle her, but it can be understood as an act of revenge (what a human feeling, revenge) for all the suffering Chris has endured. In the end of Candyman, Brianna is forced to summon Candyman, causing the death of dozens of police officers. She does it because she sees that she has no way out, and that the police, after brutally murdering Anthony, force her to declare that he threw himself on the officers. But this leads to an unavoidable question: in both films, to what extent is such violence justified? It is understood as an act of saturation on the part of the black population, and of course the amount of rage that our protagonists accumulate over racial injustices is more than understandable, but to what extent is this portrayal of violent anti-hero protagonists beneficial to the community? Is violence the only way out?

Clearly the ending of Get Out is much more hopeful than that of Candyman. In the end, Chris kills the family that held him captive and manages to escape. However, Peele has admitted that this was not the original ending. There is an alternate ending in which the police arrive at the end, when Chris strangles Rose. He is arrested and locked up for killing Rose’s family. No doubt the alternative ending feels more real, considering the contemporary police brutality towards the black population, but Peele did not want to fall into the character’s defeatism, considered by many to be a wise decision (Goldberg, 2017).

Candyman, on the other hand, has a more bittersweet ending. After brutally murdering Anthony, the police arrest Brianna. In the car, a policeman threatens Brianna: either she declares what they want or they lock her up. Brianna, seeing that she has no other way out, sums up Candyman as a last resort. Candyman comes to life in Anthony’s body and kills all the policemen. In a final scene, as Brianna watches Candyman, the lights of the approaching police cars can be seen as a somewhat discouraging metaphor. Brianna may escape, she may not. At what cost? Is Candyman really what the African American community needs? In the end DaCosta keeps moving in this ambiguity, leaving the viewer to draw their own conclusions.

Even though they do it in a very different way and they don’t necessarily cover the same topics, as it can be seen, both films denounce certain systematic behaviours and injustices. And this was one of the main reclaims in their respective marketing campaigns, as a way to engage with contemporary audiences.

Apart from Universal’s typical horror film marketing campaign, Robert Marich remarks how “the studio mounted a parallel campaign punching up Get Out’s serious cultural commentary with a different messaging and placements outside of typical horror-film media” (2017).

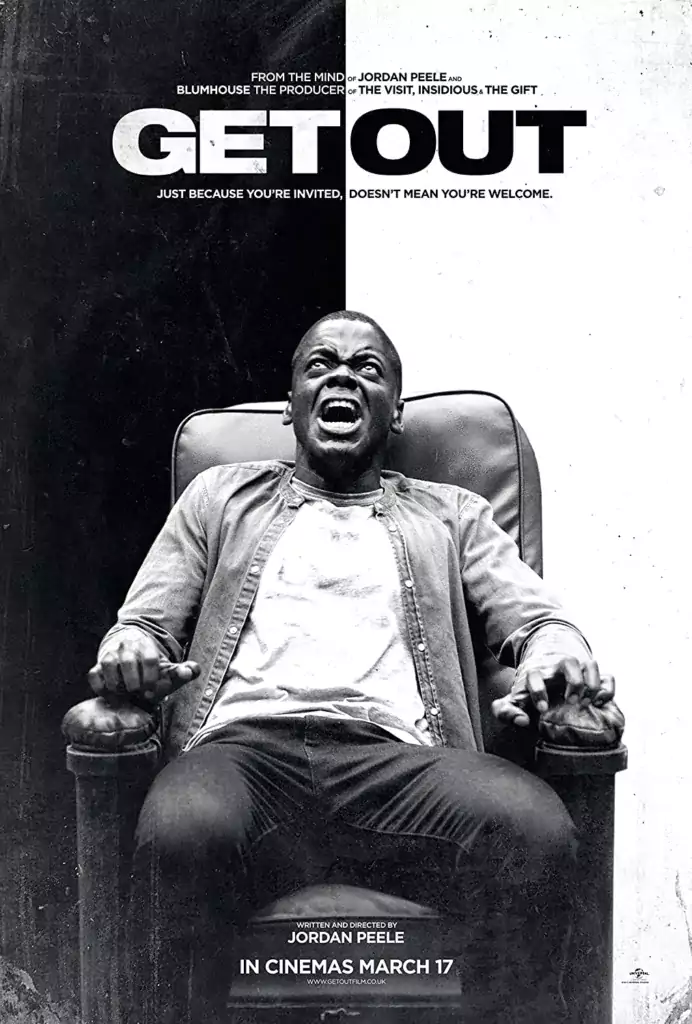

If we take a look into its promotional content, we can understand what Marich refers to in his article. The poster, for instance. Just below the title we can read the promotional catchphrase: Just because you are invited, doesn’t mean you are welcome.

Notice how the only colours used are black and white.

“Ce n’est pas parce que vous êtes invité, que vous êtes le bienvenu” translates to “Just because you are invited, doesn’t mean you are welcome”

This phrase is much more than just a promotional gimmick; it portrays a social reality. The USA is the land where thousands of black people were “invited” to come, but not welcome. They came as a workforce; as slaves.

Another interesting artistic choice in the promotional material is the colour range. Everything is either black or white, creating a dualism whose meaning is not hard to imagine: a racial and cultural clash.

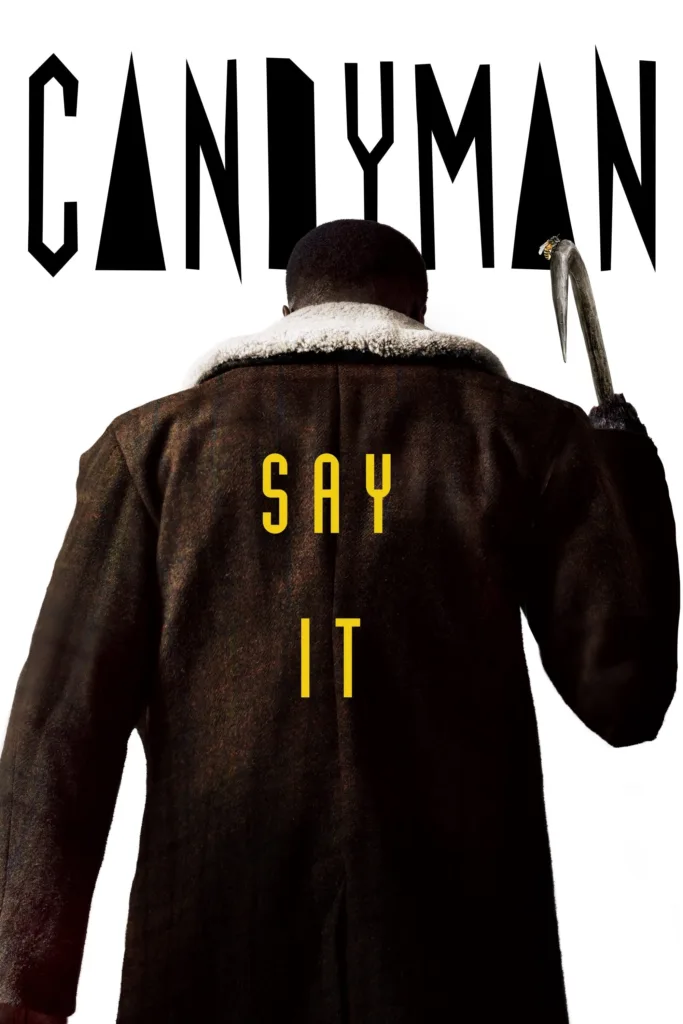

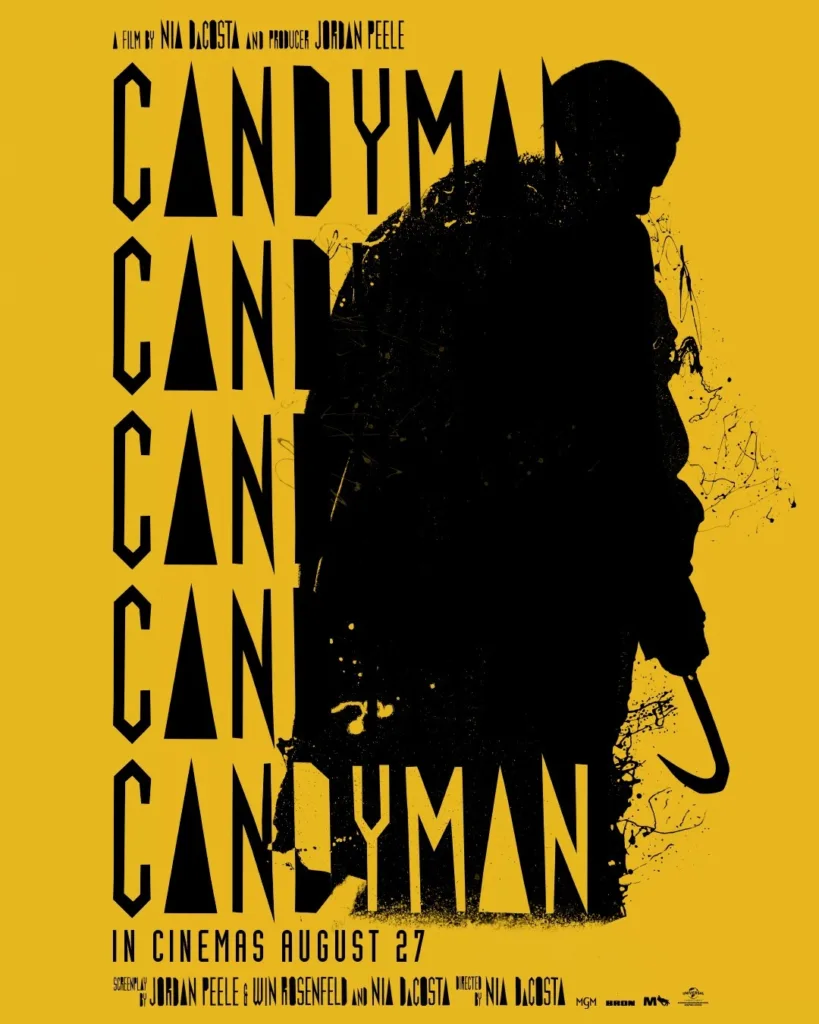

As far as Candyman is concerned, it stands to reason that Jordan Peele’s involvement was one of the biggest promotional draws, given the gigantic success he had with Get Out and Us. However, Peele is not the only reason for the film’s success. It’s worth noting the impressive social media campaign they ran.

In research from D’Alessandro: «Social media exploded for Candyman, according to analytics firm RelishMix, which measured a total reach of 144.1 million before the film’s release. Candyman’s SMU (social media unit) across Facebook, YouTube views, Instagram, and Twitter was close to 40% above the horror genre average” (2021).

They also released a Snapchat lens and in Chicago there was a stunt activation that dared those passing by to come into a mirrored booth to say “Candyman” five times. Peele also encouraged people to tweet #Candyman five times, in order to summon him. This helped the film to become a trending topic on Twitter (D’Alessandro, 2021).

This just goes to show how essential it is to have a good digital marketing campaign in the contemporary film industry. Especially because through social networks you have access to the younger generation, which, with the rise of streaming platforms, don’t go as much to the cinema. The weight of social media is huge, and can guarantee that a film will be a success before it is even released.

Candyman was sold to audiences as a regular horror film, and unlike Get Out, the marketing campaign did not go out of its way to convey the film’s political message. Different approaches; Candyman a more conventional one within the horror genre and Get Out a more political and even «provocative» one, as it highlights more obviously the duality mentioned above.

The conclusion of this comparative study is clear: despite marked differences in the marketing campaigns, and in the type of horror shown (one more slasher and the other more psychological), Get Out and Candyman have an essential characteristic in common: they engage with contemporary social and racial issues. Get Out focuses more on denouncing Post-Racial Liberal America, with subtle references to the history of slavery; Candyman, on the other hand, denounces gentrification and police brutality. It could even be said that the two films complement each other quite well, as they speak to the same general and abstract theme (racism in contemporary America), but they have a different focus and distinct priorities.

If you have liked the article you can consider donating the equivalent of a coffee in order to support us 🙂

Bibliography

- Bakare, L. (2018, February 22). Get Out: the film that dares to reveal the horror of liberal racism in America. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/feb/28/get-out-box-office-jordan-peele

- Campbell, B. A. (2021, June 13). What is Black Lives Matter and what are the aims? BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/explainers-53337780

- D’Alessandro, A. (2021, August 21). ‘Candyman’ Makes The Box Office Taste Good With $22M+ Opening. Deadline. Retrieved January 10, 2023, from https://deadline.com/2021/08/candyman-posts-sweet-thursday-night-with-1-9m-1234823246/

- Farrell, F. (2022, September 8). Candyman: Why the Original and 2021 Sequel are Important Social Commentaries in Horror. Movieweb. Retrieved January 10, 2023, from https://movieweb.com/candyman-important-social-commentary/

- Feel, D. D. (2021, September 1). Candyman: A Horror Classic Filled With Social Commentary. Taji Mag. https://tajimag.com/candyman-a-horror-classic-filled-with-social-commentary/

- Gentrification: Why is it a Problem? (2021, April 23). ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/gentrification-why-is-it-a-problem-5112456

- Get Out. (n.d.). Box Office Mojo. https://www.boxofficemojo.com/release/rl256280065/

- Get Out Explained: Symbols, Satire & Social Horror. (n.d.). The Take. Retrieved January 10, 2023, from https://the-take.com/watch/get-out-explained-symbols-satire-social-horror

- Goldberg, M. (2017, March 3). ‘Get Out’: Darker Alternate Ending Revealed by Jordan Peele. Collider. Retrieved January 10, 2023, from https://collider.com/get-out-alternate-ending/

- Landsberg, A. (2018). Horror vérité: politics and history in Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017). Continuum, 32(5), 629–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2018.1500522

- Marich, R. (2017, March 22). ‘Get Out’ Marketing Tapped Into Relationship Between Racism and Horror. Variety. Retrieved January 10, 2023, from https://variety.com/2017/biz/news/jordan-peele-get-out-marketing-racism-horror-1202012833/

- Moiz, A. (2021, December 10). Get Out film analysis- Negrophilia, race-relation and the new dynamic. Medium. https://medium.com/@abdulmoiz168/get-out-film-analysis-negrophilia-race-relation-and-the-new-dynamic-b64f6ed8095f

- Monkeypaw Productions. (n.d.-a). Retrieved January 9, 2023, from https://www.monkeypawproductions.com/productions/get-out

- Monkeypaw Productions. (n.d.-b). https://www.monkeypawproductions.com/productions/candyman

- Nolfi, J. (2022, July 13). Jordan Peele says Nope explores race through the lens of “Black people in a flying saucer film.” EW.com. https://ew.com/movies/jordan-peele-reveals-nope-explores-race-in-black-people-flying-saucer-film/

- The 90th Academy Awards | 2018. (n.d.). Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. https://www.oscars.org/oscars/ceremonies/2018